Risky Business Requires Active Operators

It’s tempting, as developers, to consider automation an absolute good. We are, after all, paid to automate work. But as the complexity of a system passes some hazy, ill-defined threshold, we need to be very clear about the risks of automation in order to successfully and safely wield its power.

As the co-founder of Skyliner, a continuous delivery launch platform for AWS, I’m obviously convinced of the virtues of automating huge swaths of traditionally manual administration tasks. I mean, I helped build a product which spins up a full multi-environment AWS architecture at the press of a button—so why am I counseling caution?

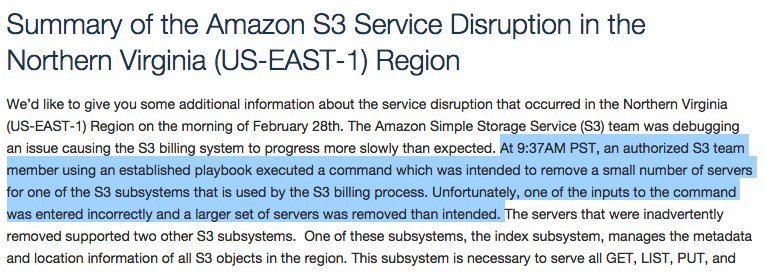

You had one job

It doesn’t take much for a system to become complex, especially when you take into account its human operators. Unlike simple systems, which can often be analyzed in terms of failure probabilities, the safety of complex systems must be considered holistically: that is, human operators included.

Automation, by removing human intervention from a task, removes the possibility of human error. Unlike a human operator, a Roomba never gets bored of vacuuming your living room, never goes on vacation, and never takes a sick day. But automation also removes the possibility of human error correction. Unlike a human operator, a Roomba will diligently paint your floors with the unexpected mess your new puppy left in the hallway. As a result, in order to build safe automation we need to consider the role of human operators in keeping complex systems safe.

When good days go bad

It’s worth noting that complex systems aren’t homogenous blobs of complexity. Some components and their activities are relatively straight-forward and some are more complex. When looking at change boundaries and automation, we should focus on those with a higher degree of downside risk which can’t be effectively hedged with automation.

For example, launching an EC2 instance has a small amount of downside risk—if it doesn’t come up cleanly, you’re paying for a useless instance—which can be very effectively hedged by using auto-scaling groups. In contrast, deploying a new version of your application to production has a large amount of downside risk—if the new version contains a subtle but horrible bug, you lose money—and this risk can’t always be hedged via blue/green deploys, canary deploys, or other types of automation.

Around these kinds of change boundaries, where the downside side is high and correctness can’t be automatically verified, we must ensure that our systems keep humans operators active. After all, they’re the only ones who will be able to detect and respond to such incidents to keep the system safe.

On the care and feeding of human operators

An active human operator is one who:

- is aware they are crossing a change boundary

- understands doing so may cause an incident

- is prepared to respond should one occur

In order to make human operators aware of change boundaries and their ambient risks, we must design automation systems which require their active participation in order to perform some actions around those boundaries. If a system is purely autonomous, any distinctions between safer and riskier actions inside it are invisible to a human operator. Similarly, actions performed by human operators should not traverse those change boundaries as an unintended consequence—they should be explicitly labeled as such and not intermediated by other, unrelated actions. By making change boundaries visible and explicit, we also help prepare human operators to respond to possible incidents. The more proximal an action is to its effect, the easier it becomes for us to reason about the immediate cause of an incident while it’s happening.

A combination emergency brake/gas pedal

For example, consider the relatively common practice of running pending database migrations as part of a successful deploy. On the happy path, this is a huge time-saver, and removes the potential for human error: never again will Gary forget to run his goddamn migrations! Off of the happy path, though, this type of automation can make incidents more likely and harder to respond to.

To begin with, this combines the crossing of two risky change boundaries in a single action. Database migrations, especially on large, live databases, are notorious for causing incidents. A poorly-written migration can take milliseconds on a developer’s laptop, seconds in QA, and hours in production, all while holding an exclusive lock and thrashing the disk.

Coupling these two actions not only increases the probability of failure, it also obscures their connection, which slows down incident response: a deploy is centered around the application, not the database, and a responder will be primed to look at potential bugs in the application before considering the possibility of a problem with the migration.

Further, it complicates any automated responses to deploy failures in general. Any attempts to restore the system to safety must take into consideration not only that the last deploy may have modified the application’s external dependencies, but also that a migration have left the database in an indeterminate state, requiring manual intervention.

Putting the pilot in “auto-pilot”

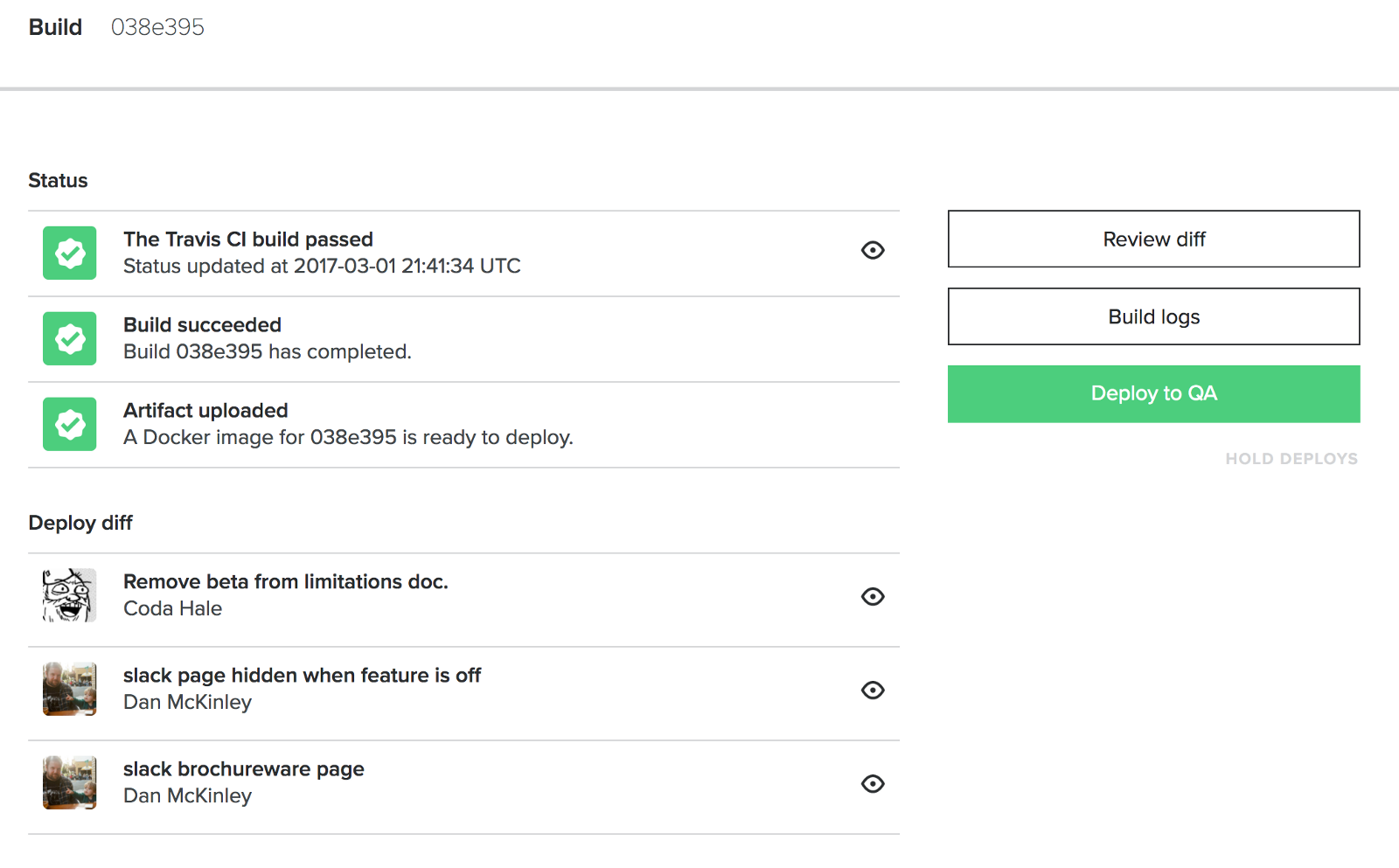

In designing Skyliner, we intentionally chose to make deploying changes to production an active process. By default, Skyliner will build commits and deploy them to QA when you push them, but promoting that build to production requires an actual human to push a button.

We also chose to avoid making that button press on your keyboard. We’re very familiar with command line tooling for deploys, and while command line tooling is amazing for automation, it often does a very poor job of actually engaging human operators in considering the surrounding context of an action:

Unlike a purely automatic system or a command line tool, Skyliner places users in an environment which primes both their expectations of what will happen when they push that button and their situational awareness of events after they push that button:

Making changes to complex systems is inherently risky, and only some of that risk can be mitigated by automation. Managing the remaining, necessary risk is the job of human operators like you and me. Safe, successful automation must empower us, not relegate us to the sidelines.